Add description, images, menus and links to your mega menu

A column with no settings can be used as a spacer

Link to your collections, sales and even external links

Add up to five columns

Add description, images, menus and links to your mega menu

A column with no settings can be used as a spacer

Link to your collections, sales and even external links

Add up to five columns

A column with no settings can be used as a spacer

Link to your collections, sales and even external links

Add up to five columns

A column with no settings can be used as a spacer

Link to your collections, sales and even external links

Add up to five columns

The Truth About Processing: Washed, Natural, Beyond...

February 02, 2023 7 min read

In light of our recent release One Coffee; Two Methods, which features a single origin Rwandan coffee from the Ibisi Mountain Hills washing station, processed as a natural and as a washed, we thought it would be helpful to cover what the heck that even means. So...

WHAT IS PROCESSING?

A complicated question, as it is defined differently across coffee regions. However, it is a crucial step in the production of coffee at origin. In brief, it is a post-harvest technique implored and vastly manipulated in order to reach one goal: turning coffee cherries into dried green coffee seeds. Fermentation plays a huge role in any style of processing and the quality control during that fermentation will greatly impact flavor, acidity, complexity, and body of a coffee!

There are no governing bodies administering standardization over styles of processing and usually the most common and rudimentary defining variable used to categorize coffee processing is: how much skin/pulp was in contact with the seed during drying.

When I first learned about coffee processing, I was told: full fruit and skin in-tact during drying made it a natural process, partial fruit/pulp exposed during drying made it a honey process, and no fruit/pulp (dried only in parchment) made it a washed.

Many folks in the industry have repeated these terms without actually understanding what is happening to the coffee. Guilty! The result is that we have colloquially categorized complex processes into arbitrary and oversimplified half truths used as marketing tools.

WHY IS ANY OF THIS IMPORTANT?

We are at a stage in our industry where consumers (and even baristas) might know that they like Guatemalan coffees, but don’t yet know that coffee is a fruit. When we don't know the significance behind the production, coffee holds less value and, honestly, pricing makes less sense. We want coffee to be valuable - and sustainable - beyond its utilitarian goodness. Meaningful and accessible education has been sparse, but if you’ve been sipping the specialty coffee kool-aid for some time, you have probably run into unfamiliar vocabulary!

With limited understanding of processing and limited subject language, we dictate the verbiage used on bag labels and in-turn dictate the style of processing present in the market by perpetuating purchasing habits that trickle through the supply chain. Those habits impact the people who produce our coffees and, sometimes, negatively.

If we gave you a new perspective on flavor and production, could we open your minds and your palates to more experiences? Could we inspire conversation? At the very least, we want you to feel happy with your coffee choices and confident about where you put your dollars.

BUT FIRST, FERMENTATION:

Although we don't consume a fermented liquid as an end product, all received coffees undergo fermentation. To understand any past or future anecdotal language created around processing, it is helpful to familiarize ourselves with the biology behind it. Fermentation is an anaerobic metabolic process utilized by yeast and bacteria to get energy. Microorganisms are everywhere and this organic system of consumption can start even before coffee cherries are harvested. The available microbial populations will vary based on health of ecosystem, temperature/climate, and location and they will utilize oxygen in different ways, contributing their own combination of acids and perceived flavors - none alone will assume the job title of Sole Flavor Provider. Yes, I made that role up.

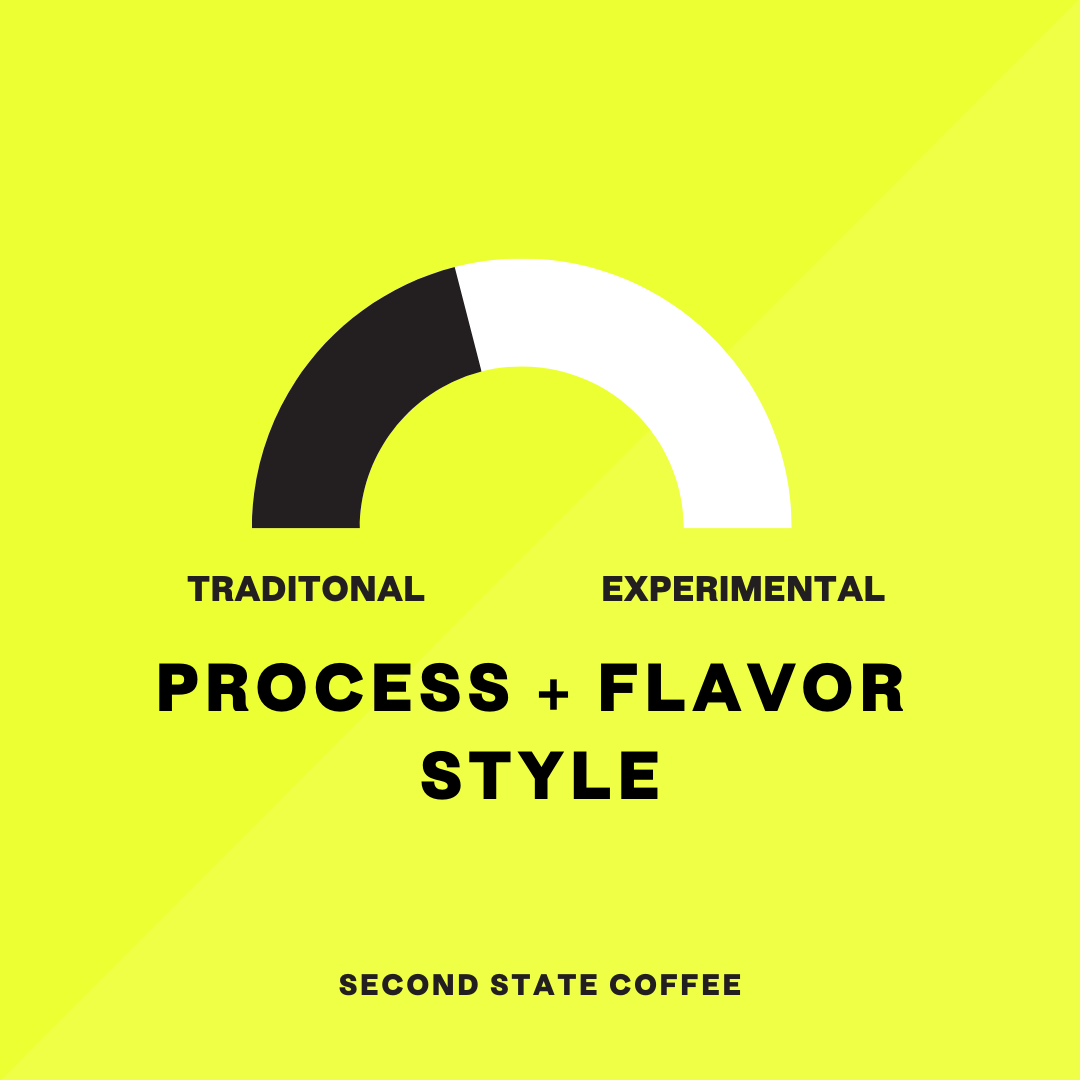

Positive or negative flavor attributes can hinge on control (or lack of control) of the variables surrounding equipment, water, mechanics of washing/de-pulping/drying, storage, and environment. Some of the methodologies used are born out of tradition, necessity, access to natural resources, and regional climate; others are derived from financial opportunity, experimentation, market demand, and drive for differentiation.

In defining the processing style, we will take a look at variations on pulp/skin removal, variations on environment, various inoculations and additives, variations in time/contact.

If you want more detail and scientific nitty gritty, you should be following processing expert Lucia Solis. If you want amazing visuals, see Cafe Import's library of processing videos. If you want one of the absolute best comprehensive glossaries, check out Christopher Feran's work. For now, we will provided this linguistic starter guide.

Please use the educational image from Sweet Maria’s as a reference for descriptions.

DRUM ROLL PLEASE... A PROCESSING GLOSSARY

Natural - aka “Dry Processed” a coffee dried with skin and fruit intact, pulp is not removed. Dry process coffees may have been manipulated through additives or environment, while "natural" has typically been used to reference a coffee that did not undergo any additional fermentation steps - simply: picking, sorting, drying. They are often described as sweeter, fruitier, and fuller bodied; though these descriptors are not always present.

Washed - a quick and efficient method in which skin and pulp are removed from the coffee cherry (de-mucilaged) and then the parchment covered seed is dried. Some washed coffees have mucilage mechanically removed and some allow removal through a fermentation to break down mucilage before being washed. Fermentation techniques and environmental constraints vary widely! In some areas, producers differentiate mechanical pulp removal as 'washed' and underwater/wet-fermentation as 'fully washed.' You may see coffees that have been held in their exposed mucilage in dry, open-air tanks referred to as 'dry-fermented.' Typically described as having bright, clean flavors and caramel like sweetness.

Honeyed - fruit skin is removed and some percentage of the pulp/mucilage is left on during the drying process. The percentage of present mucilage lends to associated names: white (the least amount) > yellow > red > purple > black (the most amount.) This coffee style, which allows for faster production and lower defect risk than a dry-process, may present the body of a Natural and the clarity and acidity of a Washed.

Expanding Our Vocabulary

Wet Process - If the skin is removed at any point during processing, it’s a wet process. This process has often been highlighted for allowing greater perceivable detection of the differences in varietal, altitude, and terroir. Results may vary widely through changes in environment, additives like pectinase or inoculated yeasts, or multi-day fermentations.

Pulped Natural - described identically to the honey process. Pulped natural is sometimes referenced specifically as Brazilian derived verbiage born from the desire to speed up the traditionally longer “natural” process of drying. The Brazilian environment creates a profile that may be described as more nutty, chocolatey than its “honeyed” counterpart.

Brazil Natural - the process of drying with skin and fruit attached is the same as other naturals; but the environment, varieties, and harvesting styles present in Brazil impact the flavors that show up during fermentation. These are described with a “coffee-pulp” fruitiness, lower acidity, and heavier body.

Wet Hulled - a style influenced heavily by its origin and tradition, but varied producer to producer. Skin is removed and mucilage is left intact until coffee is purchased. The remainder is hulled, removing the parchment layer, and then it is dried with the seed exposed to its environment. The result is higher moisture content and flavors that are herbaceous, nutty, savory, funky, and earthy.

Carbonic Maceration - Whole cherries are placed into a sealed stainless steel vessel that is flushed with carbon dioxide, reducing oxygen in the environment. Results are described as winey, with bright red fruit flavors. Additives or inoculations may vary.

Anaerobic Fermentation - fermentation that takes place in a closed environment where oxygen is restricted to change microbial concentrations, either through CO2 produced during the fermentation or by pushing out any present oxygen using inert gases. Producers use the word 'anaerobic' in reference to environment specifically (as fermentation is already innately anaerobic). This can take place with or without the entire cherry in tact and is said to yield bright and crisp coffees. In my experience, they are often boozy and winey (similar to carbonic maceration).

Deconstructed Fermentation - "Diego Bermudez, owner of Finca El Paraiso, has developed a unique processing method that allows him to manipulate coffee using a multi-stage process to isolate and control the different phases of coffee fermentation" (Barista Hustle). This process involves painstaking cherry selection and cleaning, fermentation in a low-oxygen environment, selected yeast and bacteria culture creation, isolated and inoculated cherry juices, a marriage of components, and a finished thermal shock. The resulting coffees have pronounced acidity and intense, fruity flavors. Further reading on this is recommended for greater understanding of the extensively controlled steps involved!

Thermal Shock - usually a low-oxygen fermentation followed by highly controlled hot and cold water washing. Barista Hustle describes this well: "the temperature in the tank is briefly increased to 40 °C (~104F), to open up the pores in the parchment and silverskin and allow flavour compounds to penetrate the beans. The beans are then washed with cold water at 12 °C (~53F) to clean the parchment and rapidly cool the beans. After washing, the beans are dried in a special mechanical dryer that uses a dehydrator coupled with low temperature carbon dioxide or nitrogen to gently remove the moisture. In the dryer, the beans aren’t exposed to oxygen, and the flavour compounds aren’t destroyed by heat."

Double Washed - “Kenyan Method” The coffee is pulped, the inner mucilage exposed to its environment, and placed in a tank without additional water until mucilage is no longer adhering to parchment (see "dry ferment” above). Residue is washed away and clean seeds go back in the tank with clean water. Whether or not the coffee undergoes a marketed "secondary fermentation" is up for debate.

Saccharic/Lactic/Acetic/Kombucha/Cultured/Koji - Modern experimentations. Producers are adding specific strains of yeast/microbes/cultures to the coffee and changing environmental conditions to influence end flavors. See more detail in the aforementioned extensive glossary by Christopher Feran!

LOOKING BEYOND

As we learn new verbiage, remember we are still learning how to properly and accurately represent a coffee’s process. Until then, consider how some terms may limit our own perceptions and how they may limit producers. How can we continue to create improved language around these techniques? It may start simply with more conversation, more transparency, and more curiosity.

The environment, equipment, and wild microflora that coffee interacts with is extremely variable. Fermentation is wildly inconsistent and the time frame used to determine when coffee is “done” has had very little scientific approach across the world. More and more work and experimentation is happening and our knowledge is ever increasing. It’s important to allow this sector of coffee knowledge to keep expanding, and for those of us talking about it to continue learning about it.

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.

Also in Learn with Us!

Myth busting: Fermentation and Flavor

March 25, 2025 4 min read

Fermentation doesn’t introduce new flavors that weren’t already in the coffee. It modifies what’s already there, often in subtle but measurable ways..